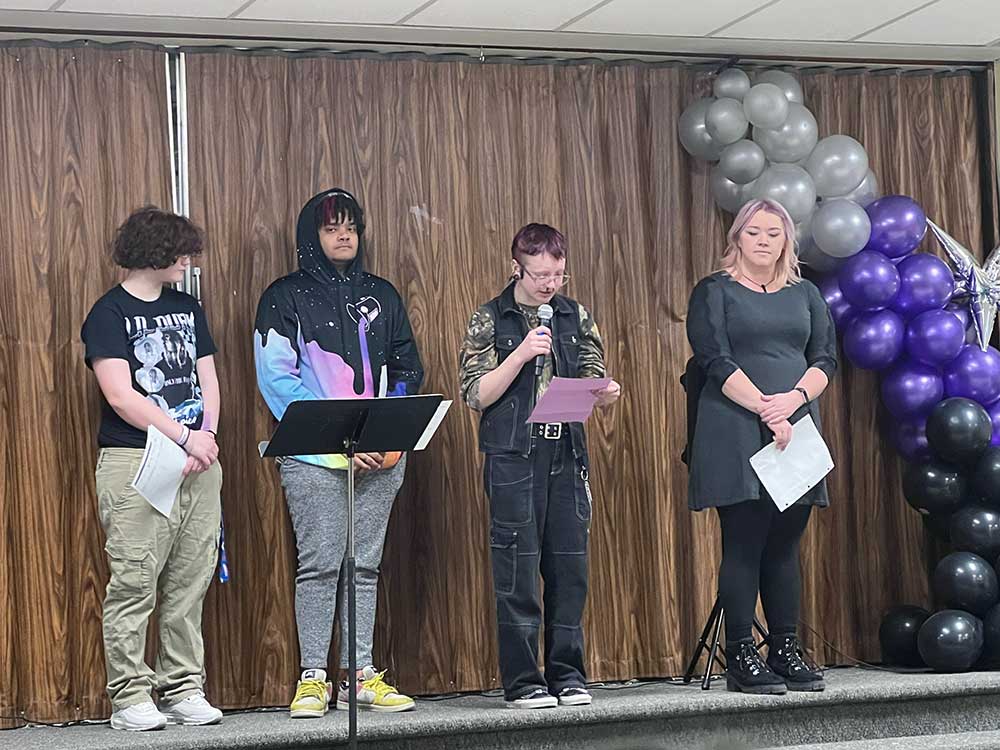

When Alex L. stood onstage at her graduation from P.E.A.S.E. Academy (Peers Enjoying a Sober Education) in 2017, the Minnesota teen’s tears weren’t just from relief at graduating. While other high school students might be thinking about college at this major milestone, Alex was simply happy to be alive. “I never saw myself living to this moment,” she says.

Now 20, Alex began self-harming at age 11, using drugs by 13 — primarily pills like Adderall and Klonopin, as well as smoking marijuana daily — and was hospitalized at 15 for suicidal ideation and substance use.

While in treatment, Alex heard about P.E.A.S.E., a recovery high school in Minneapolis, and wanted to go. She knew without a doubt that if she returned to her old high school after treatment, she would use again. Unfortunately, Alex’s parents weren’t convinced, and P.E.A.S.E. wasn’t close to where she lived. A few weeks after Alex returned to school, she used again. Only then did her parents relent, but it was up to Alex to get herself to P.E.A.S.E. To reach the school took her more than an hour, with several bus transfers.

THE OPPOSITE OF ADDICTION IS NOT RECOVERY. THE OPPOSITE OF ADDICTION IS CONNECTION.

MICHAEL DURCHSLAG, P.E.A.S.E. DIRECTOR

At P.E.A.S.E., Alex felt at home immediately. “It was really powerful to me to be able to have honest and open communication with kids my age who are trying to do the same thing of getting an education while being clean,” Alex says. “I thought if these kids can do it, I can do it.”

Michael Durchslag, P.E.A.S.E.’s director since 2007, began his career at the high school in 1995 as a social studies teacher. He credits peer connection as key to the academy’s success. “The opposite of addiction is not recovery. The opposite of addiction is connection,” Durchslag says. But the success of recovery high schools goes beyond the anecdotal: Well Being Trust’s 2019 “Pain in the Nation” report found that recovery high schools help students remain sober. Avoidance of alcohol and drugs by teens with substance-misuse issues increased to 56 percent in the 90 days after entering these types of high schools. In the 90 days prior to entering a recovery high school, this statistic was 20 percent. The report also showed that these schools help reduce school violence and increase educational attainment for teens with a past that includes substance misuse.

P.E.A.S.E. is a place where every student is familiar with what the others have been through, and where, most importantly, says Durchslag, “students are committed to being abstinent.”

P.E.A.S.E., a campus of Minnesota Transitions Charter School, was founded in 1989 to serve as a transitional school for teenagers coming out of treatment. “The students did not want to go back [to regular school],” Durchslag says, echoing the concern Alex felt when treatment ended. As a charter school, enrollment is open to Minnesota residents under the age of 21. P.E.A.S.E. was one of the first such schools in the U.S.; the Association of Recovery Schools now lists more than 30 nationwide. Durchslag feels that still isn’t enough to fill the need.

“Public schools don’t really have professionals who understand substance [misuse] disorders. There’s no requirement for training, so they just don’t understand the seriousness of the disease,” Durchslag explains.

All P.E.A.S.E. teachers receive education in substance misuse. Students are encouraged to attend 12-step recovery groups, and speakers on substance misuse are scheduled throughout the academic year. Some of the staff, like licensed drug and alcohol counselor Rufus Brown, are in recovery themselves.

Because Brown understands what the students have been through, he believes he can help provide them with social and relational skills. “If we can change how someone feels about themselves internally, they are less likely to be mean or abuse themselves in another way,” he says.

Classes are capped at 20 students, a size that allows teachers to provide individual attention to students. Small class and school size can be key: P.E.A.S.E. has a maximum of 70 students, partially due to the priority of creating customized education plans for each one.

“The majority of our students have significant gaps in their education because they have been in and out of school and gone to multiple treatments. Our teachers are aware of that,” explains Durschlag.

Indeed, Alex is grateful for the help she received in making up credits that she was missing due to substance abuse. Toward the end of her senior year, she was allowed to take mostly English and history classes, to fill in those gaps.

Durchslag is proud of the school’s results. Since he has been director, 69.4 percent of students maintained their abstinence without a recurrence of use each year. Another 19.4 percent were stabilized after a relapse. Eighty-three percent of the school’s graduates have been accepted into a post–high school program, four-year college or community college, job training program or the military.

Alex credits the academy with the stability she now enjoys. In September she celebrated four years of abstinence. She now holds a full-time job and is planning to move out of her parents’ home in the near future. “P.E.A.S.E. kept me alive to see the miracles of life and kept me going when I really didn’t want to,” she says.

By: